(An incomplete attempt at completing the line of thought of the first article )

There is a peculiar characteristic of any effort to intellectualizing an issue – it raises more questions than it answers. Probably why old veterans are quiet people, who appear reluctant to answer questions, and even when they do, the answers are short and terse, not long winded and elaborate. Anyway I think I will go a bit deeper into my mess and see what more can be found.

The “ What I should do? “ vs. “ What I desire to do? “ conflict seemed to clear the air somewhat around the warrior/saint anomaly. The ‘warrior’ is one who trains for strength, so this ‘desire Vs duty’ battle can be won. On the other hand the ‘saint’ has no battle to fight, there is no ‘desire’ and hence no ‘duty’, merger with nature is complete, all actions are spontaneous and in accord with the natural flow of things, effortlessness in everything – Ai-Ki-Do.

But all this understanding is still an intellectual exercise, efforts to integrate this in my routine run into another wall – “What I want” is easy to identify, how to determine “what I should”?

A warrior is steadfast and consistent in his actions. But when I am not sure of what determines correct actions, how can I be steadfast. If there is any lingering doubt, all spontaneity is lost, the strength of purpose actually leaks away. Many times there have been instances where I thought I had the answers, only to find later that they were incomplete, partial and sometimes wrong.

My actions which at that time seemed to be ‘What I should do’ turned out to be ‘What I should not have done’ later.

None of the warrior codes seem to leave any space for growth. As I age, my perspective changes. Some things I did, when I was young, now seem inappropriate. So what to do. Does a Samurai cut his belly open when he is old and finds that he did something in his youth that seemed absolutely correct then but now appears inappropriate.

Course correction is an integral part of life. The right path seems to be so narrow that I am always going this way or that. Slightest gap in alertness and the mind goes on a tangent, and when I regain my balance the boat is so off course.

I have no answers, not even an outline or part outline of one. But some possible patterns have emerged. I use the word ‘pattern’ because this feeling of having caught the correct thread happens during events and actions so diverse and different with no common characteristics that it must be some kind underlying pattern.

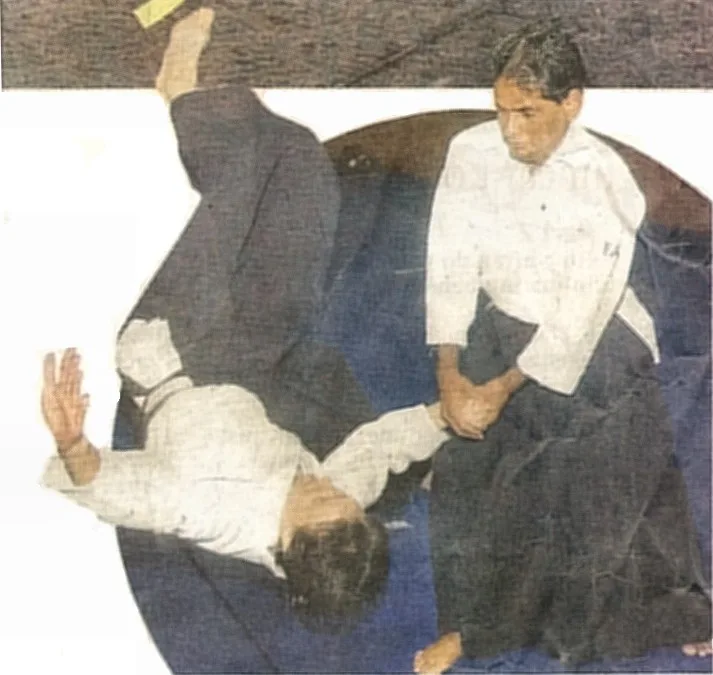

For example – my Aikido training. As a novice I tried to learn the technique like 1-2-3, you know step wise. Get out of the way, slide hand along arm and grab palm, tenkan and so on. But I found that more I concentrated on getting each step right, more I lost the overall spirit of the technique.

When using the ‘Jo’, if I tried to get my ‘Tsuki’ correct by watching each action, first stance, then move left hand like this then right hand like that … , it invariably went wrong. Instead if I concentrated on taking the Jo and thrusting it into my opponent’s solar plexus most efficiently, everything falls into place easily. Somehow the technique self corrected itself when I am simply aware of the spirit of what I am doing.

It seems that the more I focus on one thing, the other things, equally important things, went out of focus.

It seems like driving, a new driver always holds the steering tight, haunches the shoulders and concentrates hard on the front. While the veterans hold the wheel loosely, and give equal importance to central and peripheral vision, easily retaining awareness of what is in front and coming from the side at the same time.